Ennin's Diary: Travelling to China with a Japanese Monk

- Aug 6, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Sep 11, 2025

I've loved reading the tenth century diaries of Heian-era writers and poets. It's extraordinary to be able to step inside the world of a lady like Murasaki Shikibu or her counterpart Sei Shōnagon - brilliant women who occupied positions serving imperial empresses at the Kyoto court.

And so I was fascinated to discover the travel diary of the 9th century Japanese monk Ennin. Ennin was fifteen years old when he entered the large Buddhist temple complex on top of Mount Hiei called Enryakuji, in north east Kyoto. In later years, he became abbot there.

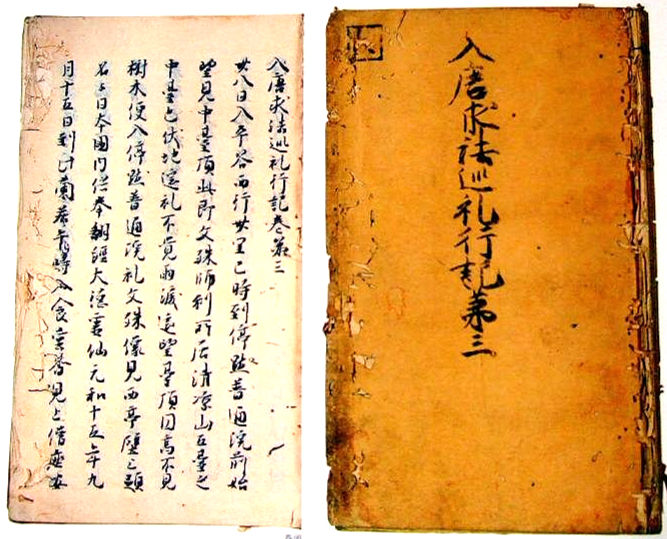

There are two manuscripts which record his travel journal - both are treasured in Kyoto. One is kept at Enryakuji, and one is kept at Tō-ji, where that dark and graceful pagoda rises just south of Kyoto Station.

Unlike the Heian ladies, who, apart from pilgrimages and festivals were largely confined to their villas in the palaces of Kyoto, Ennin records an extraordinary nine-year travel adventure, in which he is part of an embassy sent from Kyoto to the Chinese capital Chang'an (Xi'an), bearing tribute to Emperor Wuzong in 838 CE.

The diary begins with an extraordinary tale of a sea voyage starting out from near Fukuoka, culminating in shipwreck off the Chinese coast near Yangzhou. Amidst tales of mosquitoes and sickness, the party of ships (which include various ambassadors bearing familiar aristocratic names such as Fujiwara and Suguwara) are strapped together and pulled by ox along the copious network of Tang canals, until they reach the mouth of the Yangtze river.

Ennin's ship just cannot land. They spend days in fierce storms with the winds howling and mountainous seas, shaking swords, axes, and spears at the thunderbolts to send them away. (Not a good idea I think!) In the end the ship sails back for Japan, leaving the monk Ennin and his companions alone on the Chinese shore.

They repeatedly request permission to travel through China to discover 'the Law' (Buddhist scripture). Their hope is to visit the sacred site of Mount Wutai, one of the sacred peaks of Chinese Buddhism. They hope to find teachers, and Buddhist texts to copy and bring back to Kyoto in order to enrich their understanding. But the Tang bureaucracy at this time is very strict, especially over travel, and permission is repeatedly refused.

Ennin entreats by writing:

The said monk, in order to search for the Law of Buddhism, has come far across the sea. Although he has reached China, he has not yet fulfilled his long-cherished vow. His original intention in leaving his homeland was to travel around the holy land [of China] seeking teachers and studying the Law. Because the tributary embassy returned early, he was unable to accompany it back to his country, and in the end came to reside in this mountain cloister.

The detail of Ennin's diary is in the documenting of the letters sent back and forth, day after day, as he tries to secure valid documents to protect his party as they travel through the country. He is detailed about the Buddhist services that they encounter in monasteries along the way, too. And, every so often, he adds a tantalising glimpse into moments of wonder.

We learn of fascinating superstitions, such as the drawing of Buddha figures, some life-size, in order to pray for good passage. We learn of the geomantic efforts of Chang'an to pray for good weather, by the opening of the north gate of the walled city, or to pray for rain by the opening of the south gate. This reminds me of the Kyoto emperor praying to the dragon god of Yasaka shrine for rain or no rain, to end sickness or help produce flourish.

Ennin describes his perception of the painter Han Kan, who, when he paints in the eyes of a hare he animates the animal so that it can run away.

We read of Chinese citizens in the cities creating orioles for people to buy and play with.

As Ennin and his small party pass from village to village, they discover the walled city of Ch'ang-kuo. The village elder tells him the city hasn't been destroyed in war for a thousand years, yet he does not know which king resided there. The undisturbed city is an archaeological treasure.

Ennin writes: Within the walls one now finds in the ground, gold, silver, pearls, jade, ancient coins, horse trappings, and the like. There are many treasures scattered on the ground, and, after each rain, they find them.

They begin to cross high mountain passes, and Ennin describes the mountain views with a studied detail. He is nearing the sacred Wutai mountain that he has so longed to visit. We might almost be walking beside him as he walks in those mountains far from home, over a thousand years ago:

We crossed the ridge and descended gradually, sometimes going west and sometimes going south. The groves of pines on the peaks and the trees in the valleys grow straight and tall; groves of bamboos and fields of flax are not comparable to them [in straightness]. The mountain cliffs are precipitous and about to touch the Milky Way. The green of the pines reflects the blue of the skies. West of the ridge the leaves are not yet out, and the grass is not yet four inches high.

After forty-four days of walking, he reaches the five sacred summits, looking like five overturned bronze bowls. On looking at them from afar, our tears flowed involuntarily.

He is deeply moved by the beauty of the mountain terraces where he attends lectures and services and copies religious texts.

Once completed, their aim is to travel south west from Mount Wutai to the great capital city of Chang'an, in order to spend time at a monastery (he travels to the Imperial Scripture Translation Cloister) serving under a renowned and virtuous teacher who can show him the true teaching. As the party leaves Wutai, Ennin looks back to the mountains where he has stayed:

Turning one's head, one sees all of the five summits, high and round and rising far above the many other peaks. A thousand peaks and a hundred ridges, densely covered with pines and cryptomerias, stand out at varying heights below the five summits. One cannot see the floors of the deep ravines and profound valleys, and one hears only the sound of the flowing [waters] in their hidden springs and mountain streams. Strange birds soar at [different] levels above the many peaks, mounting high on their feathered wings...

Truly, Ennin's descriptions of this sacred area have been effusive. He was clearly deeply touched to spend time at this holy pilgrimage place.

It is as well that Ennin lingered over that last view of the five sacred peaks. Within weeks of his arrival at the capital, Chang'an, he witnesses the banning of Buddhism, the destruction of exquisite temples, and the persecution of Buddhist monks and nuns. This is the beginning of the end for the Tang dynasty. From its cultural flowering three hundred years before, the Mandate of Heaven is ready to bring in the new dynasty.

In Chang'an, Ennin receives a baptism and casts a flower in the Imperially Established Life Star Baptistry. Whichever deity portrait the flower lands on signifies his personal affinitive deity. When he eventually returns to Kyoto, Ennin establishes a ritual which echoes the one he participated in across the sea, up on Kyoto's Mount Hiei, but this ritual sends prayers to the Japanese Emperor's life star for the preservation of the country.

As monks and nuns are ordered to return to the lay life, and the situation for Buddhists in China's capital becomes ever more dangerous, Ennin takes his leave from his many friends who give him beautiful parting gifts, and makes his way towards the coast ready to board ship and return to Japan.

The journey is extremely arduous:

We went from waste lands into mountains, and from mountains to waste lands. The slopes are steep, the streams deep and icy, hurting us to the bone when we forded them. In the mountains, we would cross a hundred mountains and ford a hundred streams in a single day.

Eventually they are able to board ship and have wind to sail:

At dawn, far to the east we saw the island of Tsushima. At noon we saw ahead of us the mountains of Japan stretching out clearly from the east to the south-west. At nightfall we reached Shika Island in the northern part of Matsura District in the Province of Hizen and tied up.

Ennin's nine-year journey has been extraordinary, and it is astonishing to read the words of this man who lived twelve hundred years ago.

The manuscript ends with a note from the copyist:

I have finished copying this, while rubbing my old eyes, on the twenty-sixth day of the tenth moon of the fourth year of Shoo (1291) in a room in the Chourakuji.

I wonder what the old monk thought, as he sat copying this hair-raising journal with his inkstone and brush, in that temple in Kyoto's Maruyama Park!

The Buddhist Monk Xuanzang

Ennin's journey from the mountains of Kyoto to the capital of China was fraught with danger, whether he faced shipwreck, sickness, or the religious persecution which raged through the late Tang capital.

Two hundred years earlier during the Tang dynasty, a Chinese monk named Xuanzang undertook an equally perilous journey travelling west along China's northern deserts and the high mountain passes of Central Asia.

Certainly, both of these journeys that our Buddhist monks undertook required incredible bravery, fortitude, and single-mindedness. They both fervently desired to bring Buddhist teaching to the great capital cities of Chang'an (Xi'an) and Heian-kyou (Kyoto).

In Michael Wood's book The Story of China I learned more about the princely monk Xuanzang (who was tall, handsome, and sharply intelligent) and his incredible journey to where the Buddha sat under a tree and received enlightenment. I was moved to read that at the conclusion of his 16-year journey he wept.

Under the peaceful rule of Emperor Taizong he had travelled as a young monk to China's capital, Chang'an. He realised early on that to gain true understanding of Buddhist texts he needed to read them in the original scripture, as he was concerned about the potential for mistakes in the translated copies. Xuanzang's resolute focus was to bring the true word from the original Buddhist scriptures back to the Chinese capital.

Over a period of 16 years (629-645 CE), he travelled beyond the western reach of China's earthen walls and watchtowers, across fierce deserts and icy mountains. He journeyed through the countries we now know as Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, to reach the Buddhist university of Nalanda in India, and up to Kashmir and the Himalayan mountains. It is an estimated journey on foot of 25000km.

It was a journey fraught with danger, as he had no permit to travel. He travelled great distances alone, but was aided in his journey by the caravans of merchant travellers crossing the vast plains on the Silk Routes.

Xuanzang's quiet brilliance was sought by kings along the journey. His journey was extended by periods of teaching.

Xuanzang is known for his far-reaching contributions to Chinese Buddhism, his desperately hazardous journey to the Indian subcontinent, and his extraordinary efforts to carry a great many Indian texts to China, and his translations of over seventy of them.

This man returned to the capital with scrolls, texts, statuary, all of huge significance to Buddhism in China.

If you would like to see a wonderful representation of Chang'an, and follow the monk's remarkable journey through spectacular landscapes and cities, there is a gorgeous 2016 Chinese movie called Xuan Zang available on Amazon!

Also, I was fascinated to read Arthur Waley's abridged translation of the Chinese classic Monkey (Journey to the West), which is loosely rooted in Xuanzang's story, but centres on a heroic but zany sidekick monkey and the extraordinary scrapes he frees them from!

I felt that this 16th century story read just like a Pixar movie or a modern anime, and so it was fantastic to discover this recent animated movie on Netflix called The Monkey King. It has all of the mad action which is so much a part of Monkey's story in the early part of the book when his ambition is to become an Immortal. The artwork is beautiful too!

It's an incredible story to read of the tremendous determination among these Buddhist monks, to spread the word of Buddha far into their homelands. Certainly, both Ennin and Xuanzang faced perilous situations, whether they were travelling on foot for many months, surviving shipwreck, facing religious persecution, or without water in the desert. I hope you'll agree their stories are remarkable!

This is a companion blog to our look at the Tang dynasty and its influence on Heian Kyoto. Do take a look!

Thank you for reading,

Cathy

x

Sources

Ennin, Edwin O Reischauer (translator), Ennin's Diary: The Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Law, (Angelico Press, 2020).

Michael Wood, The Story of China, (Simon and Schuster, 2021).

Wu Ch'eng-en, Arthur Waley (translator), Monkey, (Penguin Classics, 1961).

Ennin's Diary image: http://www.bell.jp/pancho/k_diary-2/2007_09_12.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31203839

Nanchan Temple, Mount Wutai: By Patrick20242023 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=148815997

Xuan Zang movie (2016) on Amazon.

The Monkey King movie (2023) on Netflix.

Comments